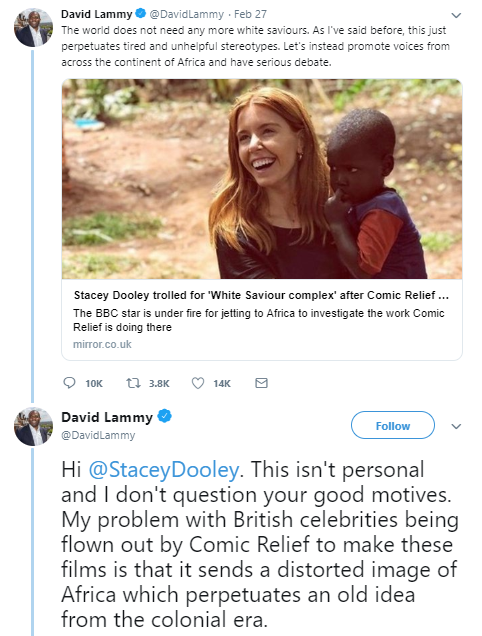

In the aftermath of MP David Lammy’s tweet accusing Comic Relief of “poverty porn” and promoting “tired and unhelpful stereotypes” we thought we would take some time to reflect on our very own Project Gambia – our twenty-year old link to the Brikama area of The Gambia. We should preface this with the fact that we appreciate how much things have changed over the last twenty years, in terms of attitudes and biases towards gender, race and sexuality; you only need watch an episode of Friends where you will find yourself cringing at some of the language used two decades ago! We have no intention to criticise people who have been involved in running or working with Project Gambia over the years; those people have worked incredibly hard to build up relationships which continue to this day.

What is “Project Gambia”?

For the uninitiated, Project Gambia came about when teachers Paul and Vanessa Buckley had a chance encounter with tour guide Alagi Bojang on the beach in Kotu, and asked him to take them to see the ‘real’ Gambia, away from the tourist area. The three of them went on to form a strong staff team, who organised links with various schools including the Kunta Kinte School in Brikama, and took groups of sixth form students out to work with the children of these schools. Over the last decade we have built up a strong relationship with the Darul Arkam School in Brikama, and its headteacher, Mr Njie.

Project Gambia receives a proportion of the school charities money, in addition to doing our own fundraising. All of the money raised by The Grange community goes directly to Alagi in Brikama by bank transfer. The only administrative cost is the cost of the bank transfer which the bursary arranges for us. According to a report commissioned by Channel 4, on average charities spend 30-40% of their income on administrative costs and fundraising, so it’s great that we can ensure 100% of your money goes straight to Alagi. The twenty students who make up the team each year pay for their own flights, meals and accommodation and staffing; their costs are entirely independent from our ‘charity’ pot.

We feel the most important thing about this trip is not the project work, it is the chance to listen to Alagi and the other people we meet, and to learn about the Gambian culture and compare it to ours. What can we learn from these people and take back to our lives in the UK? The trip is a cultural exchange; while we do leave behind material goods of which we have plenty, we take away an equal measure of knowledge and understanding which has certainly changed the way our staff and students think about life.

What are the aims of Project Gambia?

The word ‘project’ in ‘Project Gambia’ could at first glance sound patronising and like we are trying to ‘fix’ a problem, but we see this word referring to Alagi’s plans for his community. He is very much in charge of many sub-projects such as setting up barbering and hair dressing businesses, putting students through university, setting up wheelchair users with jobs selling phone top ups amongst other schemes! Mr Njie is also very much in charge of his own ‘project’ at the Darul Arkam School; he has a passion for extending his school to provide more accommodation for the older grades, and along with his community and our community has purchased a plot of land, cleared it and built one classroom block so far.

As far as our aims go, we aim to support the education of people in The Gambia first and foremost, and so all of the money we have raised in recent years has gone into the building of the Darul Arkam School. According to Mr Njie, “we were like a little seed, germinated and watered by The Grange School. We came out like a flower, and we will become a big tree.” We do not aim to make the Darul Arkam School dependent on us or to control it in any way, but we aim to share a small amount of the material goods we have with our friends to try and make our two communities more equitable.

The Darul Arkam School

Going back to David Lammy’s argument; he appears not to be against aid, but how the aid is given and received. He wants to ensure African people are in charge of their own communities and “promote voices from across the continent of Africa”. In comparison to some similar trips we think we do well on this front, probably because we have a long established sister school rather than visiting different places each year. Alagi and Mr Njie are very much in charge of what we do each year; Alagi has the ideas and asks our school community to provide the material resources to make his plans come to life. Both men regularly send over videos presented by themselves to show us what they have been up to; they are the voices of Project Gambia. Despite our schools sharing a similar vision, Mr Njie runs his school his own way. The Darul Arkam is an Islamic school and teaches Sunna and The Quran, as well as a range of subject common to our school, where as The Grange school has a Christian ethos. We would never dream of interfering with the way Mr Njie runs his school!

Do the people of The Gambia need our help?

In short, no, the people of The Gambia do not need our donations. As Alagi pointed out to the team this year, his community are not starving. However, Alagi is very keen that we continue to bring over material goods as well as our friendship, to allow him to set up his community with more opportunity and to make our two communities more equal.

Alagi told us; “Aid should be about helping someone to help themselves. If people are going to be spoon fed then it will take away their opportunity to develop for themselves because they will rely on that aid. But if the aid helps people to help themselves I think that is a fantastic help. That is what I think!”

We told Alagi about the David Lammy / Comic Relief situation and asked his opinion. He said, “I think it is good that people come and donate, but the most important thing to think about is where is your donation going and why are you donating? Some people are donating from their hearts and want to help, but some people come to The Gambia like Father Christmas and want people to see what they are doing and just want to have photos with the babies. The way you people do it is good; you go to people’s compounds to see them and it isn’t a show and you don’t just want to take pictures of holding babies, you want to meet people.”

Are people in The Gambia worse-off than in the UK?

This obviously depends on your thoughts about what is necessary to live a happy life!

The average income of someone in The Gambia is around £7000 compared to around £28,000 in the UK and £57,000 in the UAE. The two key industries supporting their economy are the production of peanuts (dependent on the weather that season), and tourism (dependent on political stability). The majority of the population do live a hand-to-mouth existence with 48% of the Gambian people living in poverty compared to 15% in the UK. The maternal mortality in The Gambia is almost 100 times higher than the UK, with far fewer hospital beds relative to their population. But this is hardly surprising given how The Gambia’s history of being exploited by western countries has left it in huge debt. Ironically when slavery was abolished, slave masters were compensated for their loss of ‘property’ but the countries the slaves were taken from were never financially compensated. They have also had a history of a corrupt government in recent times, with the former president taking money for himself. In an ideal world, these debts would be written off by our government and The Gambia would be financially compensated for the loss it suffered at our hands making aid unnecessary; lobbying our MPs is definitely something we could look into in the future.

However, money isn’t everything! There are a great many things in The Gambia that are much better than the UK, which we should learn from. The family structure in The Gambia is much more close-knit, and the young and the elderly are given care close to the heart of their families. The people we have met in The Gambia have a much better idea of work-life balance than we do. In The Gambia it is incredibly rare to see people struggling with the effects of alcohol, whereas six minutes walking through Manchester city centre would have you see dozens of people struggling with drug and alcohol dependency. Our students quickly notice how Gambian children have an incredibly positive attitude to their education, and may of our students comment about how ashamed they feel having moaning about boring lessons or teachers!

People in The Gambia seem to be more tolerant of people’s differences in religious beliefs; Christians and Muslims live side by side, join in with each other’s religious festivals and inter-marry. And Gambian people are so open and generous of spirit around strangers; it takes some time to realise not everyone here is trying to sell something! We have had some lovely conversations with strangers about all sorts on the beach, and when wandering through villages. When was the last time you struck up a long conversation with a stranger in Manchester?

What have we been doing to reduce the portrayal of Africa in a negative light?

This year we have made a concerted effort to ensure our students know that the gift bags we give out are thank you presents for people’s help and hospitality, not charitable gifts. This is the same practice seem worldwide when someone welcomes you into their home, or gives you help. We gave these to the teachers at the Darul Arkam School who came in during their holidays to help us work with their students, to our drivers, to the fruit ladies on the beach for looking after us, and to the families we met on Landrover day who welcomed us into their homes.

We have asked students to think about the way their photos could promote lazy stereotypes of Gambian children as being poor, neglected, dirty or poorly educated and in need of ‘rescue’, and they have been very amenable to this, though we could do more prior to the trip to teach them about the colonial history of The Gambia and these stereotypes. We have been much better this year at gaining consent for photos from the people we meet, but still have a way to go in this regard. We have been guilty in the past of using cute babies as prop, which we have learnt from. On the whole, our social media profiles only show photos of our students with their genuine friends, who they know by name. When our students write up their blog for the day, we have found a few stereotypes creeping through, such as people being referred to as “having nothing” when the students mean they have little money. We have been trying to correct them and point out all of the wonderful things many of the people in The Gambia do have, such as community, pride, happiness and tremendous attitude to education.

A few years ago we asked the students to think about their dress. If you look back at photos from a decade ago you will see our girls posing for group photos wearing shorts and vest tops, next to Darul Arkam students dressed in hijabs and chadors. Since then, we have suggested to our girls that they think about their dress (although we have always promoted their right to make a conscious choice about their dress) and they have all chosen to wear long, loose trousers and t-shirts which look much more culturally sensitive.

Around six years ago, there was a terrible habit of Gambian children chasing the Landrovers shouting ‘minties’ at us, basically begging for sweets as they were conditioned to do from years of experience. We were encouraged by the Gambian drivers to throw sweets at them from the moving cars. Thankfully, this practice has stopped and we will continue to ensure we do not promote the practice of begging, and we only give out little toys to children we meet and chat to and play with.

What could we improve upon?

There are lots of things we could do better. One thing that we need to think about is our visit to the clinic which we typically do each year. Whilst Alagi always asks for material resources to support the work of the medical staff, such as Awa who works at Sanyang Clinic, it is important that our gift does not put the staff under pressure to give us a tour of the clinic. Whilst students enjoy seeing the clinic laboratories we should be much more sensitive about visiting wards and ask students to think before hand about whether they think it is appropriate to visit a labour or maternity ward and disturb new mothers. Should we really be putting these women in the position where they offer our students a cuddle with their new babies?

On Landrover day, we could do more to ensure we are expected and invited to particular compounds rather than showing up unannounced, although as Alagi always points out we must realise that as Gambian culture is much more hospitable than ours; strangers are met with genuine welcome in his community.

We used to think that some of our time in The Gambia was wasted doing activities such as visiting Banjul, Katchikally Crocodile Park and museum, Tanje Cultural Museum, Gunjur fishing village, Lamin Lodge, the monkey park, Jokur Bar, Calypso bar but have come to realise that this is, in fact a good thing as we are helping to promote The Gambia as the amazing tourist destination that it is. We tried to dissuade our students from uploading too many photos of themselves doing ‘tourist’ activities at the expense of photos at the school but now realise that these positive images of The Gambia are the ones we should be promoting. We would never expect a tourist to the UK to just take photographs of our hospitals or poorest areas!

We have appreciated the opportunity raised by David Lammy to really reflect on our own practices even more than we already do, and welcome any feedback.

M Lambert, J Masters, L Sunners and A Bojang